The Crusades carried out by Western Christendom in the Middle East (there were also Christian crusades within Europe) during the Middle Ages continue to cast a blight over the relationship between the West and the Muslim world to this day. Armies from the West are routinely labelled as crusaders, linking them with the atrocities carried by those soldiers from hundreds of years ago in their religious zeal. Those soldiers were, like the fundamentalist Islamists of today, convinced their actions were saving their souls and putting them on a direct path to salvation and heaven.

Religion was experienced differently by the people of medieval Europe. The majority attended church regularly, and it was a quite different thing than it is today. Congregants were essentially observers while priests and monks conducted the mass in Latin. Some would come to recognize the words, but most did not know what they meant. The Church prohibited Bibles from being printed in the vernacular – they considered they were the only ones capable of understanding it. They interpreted it for the people, who were never supposed to question what they were told. The first Englishman who translated the Bible into the vernacular, John Wyclife, was declared a heretic for his trouble thirty years post-mortem, and his body exhumed and burned at the stake.

Mural from St Thomas’s church in England. It depicts an ale wife hugging a demon, which has led her to serve short measures. As a result she’s doomed to hell for eternity.

Churches looked very different from what most people expect nowadays too. They were a riot of colour – the walls were covered in murals of scenes from the Bible and elsewhere. It was from these scenes that people learned their theology – when you saw pictures of what would happen to you in hell if you sinned every time you went to church, that was very real to you. And that was the medieval experience of religion – it was a very physical thing. They saw the buildings that soared to the heavens and drew their eyes upwards, they looked at the paintings in the churches, they touched relics, and in the ultimate expression of devotion, they went on pilgrimage.

From the eleventh century onwards, there was a growing middle class in Europe. They spent a large part of their increasing income on expressing their devotion, and a big part of that was religious tourism, or pilgrimage. It was a huge business; people constantly criss-crossed Europe, usually in groups like today’s package tours, collecting souvenirs from the places they’d been. The big three were a scallop shell from the shrine of St James of Compostella in Spain, a set of keys from Rome, and a palm leaf from Jerusalem.

Statue of Pope Urban II at Clermont-Ferrand, the town where he initially preached the First Crusade. (Source: Wikipedia)

Pilgrimage is the single most important influence on the origin and development of crusade. In fact, without the history of pilgrimage in Western Europe, it is possible the First Crusade would never have happened. Further, even if Urban II had managed to persuade significant numbers of milites to go to the Byzantine emperor’s assistance without preaching it as a pilgrimage, an ongoing tradition is unlikely to have been created. Later, Christians who stayed in the East managed to live relatively peacefully alongside Muslims. However, they had a constant need for military reinforcements and the best way to attract these from the West was to appeal to religious consciences. (Davis, p. 288) Therefore the new arrivals at any time were always fiercely anti-Muslim and the religious fervour of new crusaders from Europe kept up the momentum of holy war in the Holy Land, when it may have been possible to make peace. It was also largely religion that caused the divisions between Western and Eastern Christians, exacerbating the situation. Ultimately, it was partially the link between crusade and pilgrimage that undermined crusade at the end of the thirteenth century.

Pope Urban II had something much more modest in mind than what eventuated when he preached what became the First Crusade. (Riley-Smith, p. 14) He received a call for help from the Byzantine emperor, Alexios Komnenus, who was only after a few professional mercenaries to supplement his own troops in his ongoing clashes with the Seljuq Turks. Urban II saw this as a chance to sort out the problem of the French knights who’d been creating havoc in France. His idea was to create a papal army from those knights. However, he and previous popes had previously had only limited success in recruiting milites san Petri, so Urban needed another motivation when he approached them. He struck on pilgrimage.

In recent years, there had been a vast growth in pilgrimage in itself, and as a way to get physically closer to more relics due in part to the growing piety that had arisen as part of the Reform Movement within Catholicism. In particular, the numbers going on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, the centre of the Christian world and a relic itself, had grown markedly over the previous century. (Webb, MEP, p. 16) To a certain extent, the military classes had felt alienated from the groundswell of piety leading people to humble themselves as penitential pilgrims. There was also still much credence in the theory that pretty much the only people who would make it to heaven were monks. Urban though, as a product of the French nobility himself, knew how to appeal to his people. When he preached what became the First Crusade at Clermont in 1095, he called for an armed pilgrimage, with the significant sweetener of a plenary indulgence. Here was a way the militarized French nobility could serve God without completely humbling themselves in the way penitential pilgrims should, or abandoning their weapons. They could achieve salvation by being themselves. This could not help but appeal to significant numbers of them.

What Urban appears not to have envisaged was that his call to arms would be taken up by men and women from all levels of society, and this was largely due to the part pilgrimage played in the lives of all western European Christians. He had started something that he was unable to stop. Medieval peoples’ understanding of their place in the history of the world needs to be kept in mind here too, as it helps explain why things like penitential pilgrimage were so important. They believed the world was in decline, they were living in the Biblical Last Age, and the End of the World was nigh. (Flanagan, p. 19) The plenary indulgence that went along with participation in the (later First) Crusade would have awakened the desire of many to take part like nothing else could. To have all ones sins forgiven at a time when all people ‘knew’ they were filled with sin and the Day of Judgement was imminent would have been something they had not even dreamed could be possible. From the time of Urban’s sermon at Clermont therefore, crusade and pilgrimage were inextricably intertwined.

Emperor Komnenos was both scared and angry by the crusaders his so-called ally had sent him; they were not what he wanted. They were pillaging his lands and raping and murdering his people long before they even arrived at his capital, secure in the knowledge that they were on a fast track to heaven if anything happened to them. If they felt guilty in the meantime, there were many religious attached to the crusade ready to hear their confessions and bless them afresh.

Crusaders were simply armed pilgrims, as opposed to unarmed pilgrims, and to contemporaries it was only their arms that distinguished them from other peregrini. All aspects of pilgrimage – the vow, indulgence, symbolism, family tradition, reasons for participation, and who took part – were virtually the same in the sub-group of crusaders as they were for all pilgrims. The fact that contemporaries saw little difference between crusaders and other pilgrims meant the development of many aspects of crusade are mirrored in the development of pilgrimage as a whole. There were also several events that kept crusade aligned with pilgrimage. For example, the outstanding success of the First Crusade was inexplicable to people who had little idea of what was going on politically in the Muslim world at the time. Their seemingly impossible victory was from God – he approved of what they were doing and had given them the victory. (Riley-Smith, p. 99) This naturally highlighted the religious reasons for going on crusade. (In fact, completely unbeknown to them, the crusaders simply couldn’t have picked a better time to attack. They got lucky.)

Margery Kempe was an English mystic who went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages. She was famous for annoying her travelling companions with her constant crying out loud, moaning and writhing on the ground when communing with Jesus. Some tried to get her left behind at several stops while others admired her devotion. She wrote a book about her travels, which is recognized as the first autobiography in English.

Although it is impossible to know what proportion of Western Europe’s medieval population embarked on pilgrimage, it is nevertheless clear that there was a wide awareness of the practice. (Webb, MEP, p. 172) Most of the popular literature available to secular audiences was hagiographies (biographies of saints) and translationes (stories of the making of saints), both of which included numerous examples of miracles related to pilgrims. Travel books were usually accounts of crusades or other pilgrimages, both personal and second-hand. There are also numerous examples in songs and poems such as Chanson d’Antioche.

From the time it was first written in the late thirteenth century, The Golden Legend was the medieval period’s most popular book. (Shinners, p. 178) This collection of almost two hundred saints’ lives along with stories about Jesus, the Virgin Mary and the major Christian feasts, was soon translated from its original Latin into the vernacular throughout Western Europe. (Shinners, p. 178) In fact, it can probably be assumed that knowledge of the stories in The Golden Legend was the norm rather than the exception; Chaucer expected his readers to be familiar with it and following the advent of printing, it was published more often than the Bible for decades.

From the philological evidence it is also possible to make an assumption that contemporaries saw little difference between crusaders and other pilgrims, and that it was the religious aspects of crusade that most appealed. Words, phrases and symbolism conventionally related to monasticism, very quickly became part of the vocabulary used in crusade writings. (Riley-Smith, p. 37) The crusades were “the way of the cross” and “spiritual warfare” while crusaders were “the knighthood of Christ”.

On the other hand, the failure of a separate term to differentiate crusaders from other pilgrims to be established until many generations of them had been fighting in the Holy Land and elsewhere is perhaps the strongest indication that contemporaries considered the differences between them to be negligible. Urban II had directed crusaders to sew a cross on their clothing as a sign of their vow. However, it was not until the late twelfth-century that the term crucesignatus was used with any regularity for crusaders, and in the thirteenth century, crusaders to the Baltic were still being called peregrini. (Webb, MEP, pp. 19-20)

The sewing of a cross on clothing soon became synonymous with any pilgrimage to the Holy Land, not just with the armed crusaders. Those who were not part of a crusade began to sew crosses on their clothing too. These pilgrims clearly saw little difference between themselves and crusaders. A well-documented example of this is St. Raimondo Palmario of Piacenza and his mother, who sewed crosses to their clothing for their pilgrimage in the 1150s, although they had no intention of taking part in any military activity. (Webb, MEP, p. 22) In England, both crusaders and other pilgrims adopted the surname ‘Palmer’ in reference to their visits to the Holy Land of which a palm frond was the standard souvenir.

Replica of a medieval pilgrim badge from St James of Compostella’s shrine (Source: Lionheart Historical Pewter Replicas)

Other symbols were the same for crusaders as for other pilgrims too. All crusaders took a vow of pilgrimage and as such, their scrips (a type of shoulder bag/wallet) and (walking) staffs were blessed. (Webb, P&P, p. 21) The only difference with crusaders was that their weapons were similarly blessed. The blessing of Richard the Lionheart’s sword before he took part in the Third Crusade in 1190 is a matter of record. (Webb, MEP, p. 22) There is evidence from contemporary sources that the crusaders renewed their oaths while on crusade too. (Riley-Smith, p. 85)

To help us understand that pilgrimage was the main motivation for crusaders, we have to examine some of the conditions the crusaders lived under. At the best of times, a journey to the Holy Land was long, dangerous and filled with privation. Pilgrims suffered in their travels, every day and death was a constant threat. The suffering though was welcomed as a penance; by it, those partaking could feel they were earning their indulgences. This mindset of the value of suffering is evidenced by the meteoric rise of the reform orders like the Cluniacs during this period, which were noted for their austerity. (Leyser, p. 236)

If ordinary pilgrims met with hardship on their journeys, the suffering was much greater for crusaders. While any area might be able to sustain even large numbers of pilgrims travelling through their territory, an army of thousands with war-horses was another matter. Lack of food was endemic and death from starvation was frequent. (Riley-Smith, pp. 66-8) Urban himself recognized that a high level of suffering was likely. His grants of indulgence to departing crusaders call the enterprise a “severe and highly meritorious penance”. (Riley-Smith, p. 27) In Decreta Claromonterisia he says,

Whoever for devotion only, not to gain honour or money, goes to Jerusalem to liberate the Church of God can substitute this journey for all penance. (Riley-Smith, p. 29)

This plenary indulgence is partly in recognition that the suffering of the crusaders would be so severe it would be enough to serve as penance for any sins committed. (Riley-Smith, p. 28)

As already noted, the crusaders were often literally starving. However, the pilgrimage aspect of their journey was so important to them this didn’t stop them from undertaking frequent ritual fasts. During the First Crusade, they fasted on such occasions as their departure from Nicaea, before they raised the siege of ‘Arqah, after an earthquake on 30 December 1097, before the battle of Antioch, before an ordeal undertaken by Peter Bartholomew, and before their procession around Jerusalem. (Riley-Smith, p. 85)

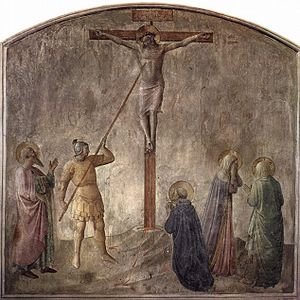

Fresco in the Dominican Monastery in San Marco, Florence showing the side of Jesus being pierced by a lance. Painted c. 1440 by Friar Angelico. (Source: Wikipedia)

In addition to the above, there are other features of pilgrimage in crusade exemplified by those on the First Crusade. Raymond Aguilers and Fulcher of Chartres both reported that “… from the time the crusade reached Jerusalem, parties of crusaders made solemn visits to the Jordan, where they underwent a ritual re-baptism.” (Riley-Smith, pp. 84-5) The collection of relics of all kinds by crusaders is well known too. From the time of the First Crusade there was a flood of relics from the Holy Land to Western Europe, creating some significant rises and falls in the popularity of different saints. Particularly renowned are the purported discoveries of the Holy Lance and True Cross by the first crusaders, both of which were purported to protect those around them from harm during battle. (Riley-Smith, pp 93-8)

However, it was in prayer and other worship that the pilgrimage aspects of crusade are most obvious. (Riley-Smith, p. 84) Masses were said regularly, with extras before every important event, particularly those where lives were at risk. All of the known chroniclers also report the churchmen taking confession at these times. (Riley-Smith, pp.82-3)

The [first] crusade struck contemporaries . . . as being like a military monastery on the move, constantly at prayer: Raymond of Aguilers twice compared the army in battle order to a church procession. (Riley-Smith, p. 84)

The churchmen also played an active role in all military engagements, as appropriate to their calling; they stood in their vestments, praying aloud, during all conflicts. Ralph of Caen reported that when a siege tower got stuck during the siege of Jerusalem (First Crusade), it was the prayers of the priests that got it moving again. (Riley-Smith, p. 84)

As can be seen, pilgrimage played a vital role in the lives of crusaders. As the Middle Ages progressed peoples’ religious foci moved more towards relics and images and away from pilgrimage; at the same time, enthusiasm for crusade began to wane. As Protestantism became more widespread, its forbidding of pilgrimage reduced crusade to the point it was no longer part of the culture in Protestant countries. There is not enough space here to fully discuss that the motivation for most people in going on crusade was religious, but all the more recent scholarship on the subject comes to this conclusion. Religion was intrinsic to the nature of all medieval people; it was the physicality of medieval peoples’ expression of their faith that led to the popularity of practices like pilgrimage; it was the popularity of pilgrimage that turned Urban II’s vision of a papal army to free the Holy Land into the ongoing phenomenon of Crusade.

Bibliography

Bainton, Roland H., Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, New York, Abingdon, 1978.

Bridge, Antony, The Crusades. London: Granada, 1980.

Crawford, Anne (ed.). Letters of the Queens of England (2nd Edition). Stroud: Sutton, 2002.

Davis, RHC, A History of Medieval Europe. London: Longman, 1970.

Flanagan, Sabina, Hildegard of Bingen, 1088-1179: A Visionary Life (Second edition). London: Routledge 1998.

Hinnells, John R (ed.), The Penguin Dictionary of Religions. London: Penguin, 1997.

Hopkins, Andrea, Most Wise and Valiant Ladies. London: Collins and Brown, 1997.

Jillings, Karen, 148.212 The Crusades – Study Guide. Palmerston North: Massey University, 2005.

Jillings, Karen (ed.), 148.212 The Crusades – Book of Readings. Palmerston North: Massey University, 2005.

Leyser, Henrietta, Medieval Women: A Social History of Women in England, 450-1500. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1995.

Riley-Smith, Jonathan, The Crusades: A Short History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

Riley-Smith, Jonathan, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. London: Athlone, 1993. (All references from this book.)

Riley-Smith, Jonathan, What Were the Crusades? (Second Edition.) Houndmills: MacMillan, 1992.

Shinners, John (ed.), Medieval Popular Religion: A Reader. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 1997.

Webb, Diana, Medieval European Pilgrimage. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2002.

Webb, Diana, Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in the Medieval West. London, IB Tauris, 1999.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider donating a dollar or two to help keep the site going. Thank you.

This reminds me of something I read in my college days:

Very cool. I have to read Chaucer about three times before I can get it, but once I do, I love it. 🙂

And I thought pilgrimage was among the more benign forms of religious piety.

It was until the idea of armed pilgrimage came along. It’s like anything religious – there are always those who take it to extremes. If everyone stuck to the happy clappy stuff, we’d all be able to get along, but there are always some who get carried away. That’s why, imo, it would be better if there was no religion at all, although I don’t think it should be banned or anything.

Yep, Government banning of religion would just then become a “religion” of heresy hunting.

I realize your post wasn’t really about this thing but it’s worth reminding people in the era of apologists, that the Crusades were wars between the Christian Empire and the Muslim Empire over land that neither of them had any historical claim on. The region where Jerusalem is was in ancient times called Canaan. Kind of like The Prairies or The Outback. And it was made up of a bunch of tiny little kingdoms. The Jewish kingdom who’s history Christianity appropriated was one of these. The Muslim conquest in the 900s A.D. wiped out all the remaining kingdoms and made that area into just a region within its empire. I sometimes wonder if people are actually aware of that. (Bernard Lewis has a good popular book about this whose title I don’t remember.) The people who live there now are the descendants of Canaanites. They aren’t Arabs. The idea they are Arabs is something they were brainwashed into as part of the Muslim conquest. Kind of how Northern Europeans see Christianity as intrinsically part of their culture and history. Even though Britain was converted to Christianity by the Roman empire. Christianity for a long time was just Roman. “Pre-Christian” European history is mostly invisible to us Europeans and European derived people. (Like you in New Zealand Heather and me and Canada. )

Anyway the Crusades were wars between two rival empires for a piece of land. The motivation for wanting that piece of land was totally religious. Making the whole thing hideously absurd. But making it even more absurd is the the bits of their two religions that made them feel what, a desire for that real estate? We’re derived from another older religion that was completely unconnected to their own. Christianity is a Greek religion full of Greek ideas. That are completely alien to the Judaism of the time when Jesus is said to have lived. Think about it a moment: he was preaching salvation from hell. To Jews. In the Hellenist period. Judaism didn’t have hell then. (The modern versions of Judaism don’t have hell now. Because they’re harking back to the original.) Islam was an Arab, as in Arabia, created religion based on Mohammed’s reported visions. There’s no intrinsic reason for it, or for Christianity, to have connected themselves to Judaism. Which raises the interesting question, why did they? If they hadn’t presumably these two religions with their humongous populations would not be teaching and preaching Jew hating now. In a word: dang. The speculation I’ve read as to why they decided to connect their religions to Judaism is because in the era these two religions were created Judaism was very old. And even in ancient times people were impressed by what to them was ancient stuff. Makes me smile. The desire to connect their religions to Judaism, which neither Zoroaster nor the later Zoroastrians felt, may also have been influenced by the fact that Judaism had a book. Which was rare and also gave you something to point to. “We have special knowledge”. But really who knows. What’s important is the connecting to Judaism is weird and might well have not happened.

The last comment that needs to be made on any discussion of the Crusades in this era of apologist for Islamist extremists is: the Muslims won. They kicked Christian ass. To hold onto a piece of land that they took as part of military conquest. So let’s remember that. And point it out when people try to pretend that the Crusades were some kind of hideous crime by the “West” against “Islam”.

Yeah, Islam did win, over and over again. The only reason most of that land was considered important by those fighting over it was religion, as you say. Neither had any claim over it. You make a lot of good and interesting points. I think it was association with The Book that was important for Christianity and Islam, but that’s obviously just a theory. Both religions appear to me to have made up myths to make themselves descendants of it, then treated it badly to disassociate themselves.

Exactly! And it’s such a mindf**k. And would make, in disguise, a great science fiction series…

Good idea! I can just see at as an episode of Star Trek or something.

Canaan was not an outpost, but at the crossroads of the great civilizations of Mesopotamia, and Egypt, and had been for 4000 years before the crusades took place. It was one of the most fought over pieces of territory in history. It was owned by many peoples in recorded history, much documented in the Torah, and no doubt many more peoples before that.

Who has a historical claim to any land? Do the anglo-saxons have any claim to England, or is it the Irish, scots, and Welsh who have the real claim? Does anyone have any historical claim to the Americas, other than the indigenous people? NZ–Maoris. But in an area as heavily trafficked as the Levant, who knows? wrt the crusades, for over 400 years the area had been in Muslim hands. Since 1187 until 1917 it was in Muslim hands. That’s a pretty good historical claim. Even the Hebrew people can be dated to no earlier than about 1200 bce. And their rule, to the extent it was a rule, was interrupted by Assyrians, Egyptians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans, ending in about 63 bce, the Hebrews/Jews can hardly claim to have actually ruled Canaan for more than 500 years

The crusades are just a proxy issue for the Israeli Palestinian conflict. They have no bearing on anything, except as a symbol. It’s an interesting story, with no relevance to today. What is relevant today is the recent (last 100 years) history of western imperialism. People still remember the League of Nations mandates, and the western dominated petroleum companies that were set up to tap the oil. And the dictatorships the west supported in Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Syria, and elsewhere. And the western imposed creation of a “Jewish State” in a land where a majority of people were Muslim. And the US/Brit “Christian Bush/Blair” invasion of Iraq, killing hundreds of thousands and setting off a conflagration that is still going on. And the savage Israeli onslaughts on defenseless Gazans, time and again, killing thousands. These things are real and alive in the minds of people (not western people because the media and the establishment don’t choose to see the truth). It’s these things, not the crusades, that matter.

As you say, at the time of the First Crusade, the land had “belonged” to Muslims for some time, although in the context of that region, they were pretty recent interlopers. It can be argued that the Crusades are important today because they’re seen as a symbol, especially within Islam, and symbols are the expression of beliefs and are what drive people. Try asking Christians to stamp on a piece of paper that you’ve just drawn a cross on in pencil and see what happens. Do it in a Catholic Church, and you’re likely to get a pretty violent reaction. Look how some Muslims react to any depiction of Muhammad. The fact that most people, especially in the Christian world, have an erroneous idea of what happened seems not to be even relevant. I bet if you did a survey in the US asking who won the Crusades, at least 70% would say the Christians.

There is a major problem with how western countries and companies have behaved in the Middle East in the last 100 years since oil made it interesting. If you step back (and this isn’t to justify it, because it can’t be justified), it’s not any different to what those in power have been doing to the weak throughout history. We’ve got to the point where we are now, and in my opinion we have to find a way to move forward. The reason the Israel/Palestine issue isn’t getting solved is because both sides are so focused on what has been done to them in the past. They want justice/revenge for what they’ve suffered. That’s perfectly understandable, but it means nothing changes. Whenever it has seemed possible to move forward, both sides become unreasonable in some way. We can argue about who is right and who is wrong and who is the most unreasonable, but none of that will fix it. We need a two state solution, but at the moment neither side is prepared to make the concessions that are needed to make that work. In the meantime, Israel continues to exacerbate the situation by doing things like building on land that’s not theirs, and Gaza funnels a huge proportion of their already too small resources into things like weapons. Neither side is able to trust the other because both sides have proven they can’t be trusted in various ways. It’s easy to see Israel as the “baddie” because they have by far the most power, and have done by far the most physical damage, but they have justifiable complaints too. I also think religion is the biggest block in getting a solution – when children are getting taught in school and on state television, as they are in the Palestinian territories, that Jews are evil, it’s makes any hope of a peaceful future much less likely. The Hamas Charter is full of revolting anti-Semitic rhetoric too.

Good summary of the situation Heather. I agree that religion, and quasi-religion, like Zionism, are major parts of the problem. But it’s also cultural. Israel, like the crusades, represents another incursion of western culture in the middle east. It hardly matters to the resident Muslims whether it is Jewish or Christian.

You made an important observation, related to Charlie Hebdo and similar incidents:t “Try asking Christians to stamp on a piece of paper that you’ve just drawn a cross on in pencil and see what happens. Do it in a Catholic Church, and you’re likely to get a pretty violent reaction. Look how some Muslims react to any depiction of Muhammad.”

Yes, no one likes to be insulted, especially regarding things that are sacred to them. I appreciate the value of humor and parody elucidating absurdities in religion, but I have little sympathy for those who insult people just for the purpose of denigrating, especially when the insulter is from the majority culture and the insulted is a minority. It’s just the SJW in me, I guess.

Have you followed Eric’s responses to our discussion and your post on the Crusades? I haven’t made much progress against his belief that Islam is and always has been a particularly vile and dangerous religion.

Hope you are well.

WTF is an SJW?

Sorry, I hate it too when people throw acronyms about. Social Justice Warrior. It’s a term I learned from Heather, which is why I didn’t spell it out. But I’ve since seen it elsewhere. As I understand the term, it is a derogatory reference to people who are willing to curtail free speech in order to protect vulnerable people from harm. Heather, want to correct me?

Thank you for that. I see so many III’s* on the internet that need to be explained that I have to wonder whether the effort of explaining after the fact mitigates the convenience of using the initialism in the first place.

*Intrinsically Idiomatic Initialisms

III. I love that!! Not sure I understand each word by itself or together, but I sense it captures something important.

Yeah III – I’d never seen that before – it’s a good one!

I’m always having to look up initials to see what they mean in on-line urban dictionaries – I just assume it’s because I’m not young and cool anymore (actually, not sure I was ever very cool) and everyone else knows except me. They can come in handy on Twitter because you’ve only got 140 characters at most. Also, although I swear in my head a lot, I don’t like to do it out loud or in writing, so saying WTF comes is useful there.

A couple of years ago when having lunch in a cafe with one of my sisters and her two young daughters. Her and I saw something a bit weird that the girls didn’t notice and I said “WTF” to my sister. The girls were trying to work out what WTF stood for, and tried all sorts of combinations. They settled on “Who’s the fatty?” So that’s what it’s become between that sister and I. 😀

That’s exactly what it means when I use it Paxton – cheers. Sorry EA Blair – I’ve probably used it sometimes without explaining it too, and I should make a point of doing so each time I use it.

I haven’t been no – I’ve been away for a few days, and it always takes me a while to recover afterwards. I’m still catching up on my e-mails. I’ll check it out sometime. I’m a bit reluctant to get involved at the moment because I’m having trouble keeping up already.

It’s hard to get someone to change a firmly entrenched belief, whatever it is, and there are certainly plenty of reasons to get anti-any religion if you look at it closely.