According to Wikipedia:

Blasphemy is the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence for God, to religious or holy persons or things, or toward something considered sacred or inviolable.

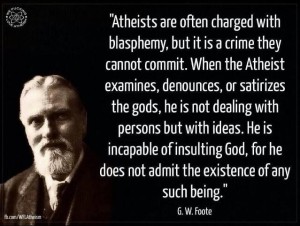

Blasphemy laws, therefore, are designed to protect religion (usually the dominant religion of a country) from criticism. They make the ideas of religion different from other ideas, placing them above other forms of expression. This, of course, is a limit on freedom of speech and expression. Many New Zealanders are probably unaware that we even have a blasphemy law, and it no doubt surprises many. They probably assume (correctly) it’s a relic from our colonial past.

Blasphemy laws, therefore, are designed to protect religion (usually the dominant religion of a country) from criticism. They make the ideas of religion different from other ideas, placing them above other forms of expression. This, of course, is a limit on freedom of speech and expression. Many New Zealanders are probably unaware that we even have a blasphemy law, and it no doubt surprises many. They probably assume (correctly) it’s a relic from our colonial past.

Iain Middleton, vice-president of the Humanist Society of New Zealand, says:

It is of interest that New Zealand’s blasphemy law was an adaption of the UK common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel that applied in England and Wales. These common law offences were abolished in 2008 by an amendment to [their] Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008. New Zealand has yet to follow the example of the UK and abolish Blasphemy Law.

Thus, we inherited our blasphemy law from the English when we were a British colony; they have moved on – it’s time we did too. Unlike us, Australia has moved on. The Australian Law Reform Commission recommended all references to blasphemy removed from federal legislation in 1991.

The law that still applies in New Zealand is based on the English Blasphemy Act (1697) which, according to Wikipedia:

(See comment by me below that includes more info from Iain Middleton.)

… made it an offence for any person, educated in or having made profession of the Christian religion, by writing, preaching, teaching or advised speaking, to deny the Holy Trinity, to claim there is more than one god, to deny the truth of Christianity and to deny the Bible as divine authority.

The decreed punishment:

The first offence resulted in being rendered incapable of holding any office or place of trust. The second offence resulted in being rendered incapable of bringing any action, of being guardian or executor, or of taking a legacy or deed of gift, and three years imprisonment without bail.

As Middleton points out:

It is also worth noting that the common law charges of blasphemous libel only protected or applied to the Church of England and anyone from Atheists, to Quakers and Methodists could be charged with blasphemous libel for questioning the tenets of the Church of England.

When the New Zealand Crimes Act 1961 was introduced, it continued to include blasphemy as a crime, punishable by a sentence of one year of imprisonment. This was despite the fact the law had only ever been used once, unsuccessfully, almost forty years earlier. It requires the leave of the Attorney-General to bring a prosecution under the Act. That leave is not readily given.

When the New Zealand Crimes Act 1961 was introduced, it continued to include blasphemy as a crime, punishable by a sentence of one year of imprisonment. This was despite the fact the law had only ever been used once, unsuccessfully, almost forty years earlier. It requires the leave of the Attorney-General to bring a prosecution under the Act. That leave is not readily given.

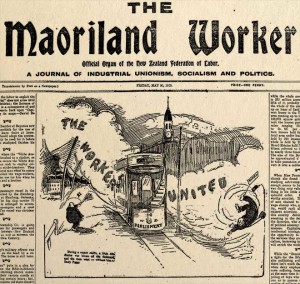

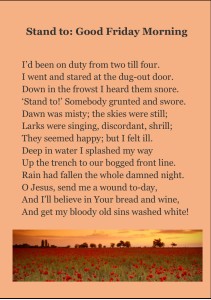

The unsuccessful case was taken against John Glover. He was editor of the Maoriland Worker, a monthly journal in support of labour unions. In the October 1921 issue, Glover (a secularist) included two poems by the English poet Siegfried Sassoon from a collection of Sassoon’s war poems, The Old Huntsman and other Poems (1918). One of the poems was this one:

The last three lines prompted the government to charge Glover with blasphemy. Specifically, the charge was, “Reviling Christ and the Last Sacrament.” The prosecution failed. The jury did, however, say “… that similar publications of such literature be discouraged.”

The most recent attempt to use the law was in 1998. (Then) MP John Banks and Father Meuli of Mt St Mary’s (Auckland) tried to bring criminal charges against Te Papa Tongarewa, the Museum of New Zealand, under the blasphemy law, now section 124 (1) of the Crimes Act 1961. Their contention was that two artworks on display at Te Papa were blasphemous. The artworks in question were Wrecked (Sam Taylor-Wood) and Virgin in a Condom (Tania Kovat).

According to the Society for the Protection of Community Standards, the Church’s application had tens of thousands of supporters. The protests were led by the Catholic Church, but they had the backing of many other individuals and groups. They claim those supporters included Orthodox Catholics, Protestants, Baha’i, Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, Jews, Ringatu, and Sikhs. There was, they said, also support from agnostics and atheists (which they claim by naming two media commentators).

There were several peaceful protests outside the museum and talk radio was abuzz. Also, many wrote to the museum individually asking them to remove the items from the exhibit.

Their application was denied by Solicitor-General John McGrath QC. He said freedom of expression was more important than the fact that many considered the two artworks to be blasphemous. Freedom of expression is safeguarded by the 1994 Bill of Rights.

So basically we have a law that New Zealand didn’t ask for, has never been used successfully. And, if it was used, it would breach the Bill of Rights. All this law does is damage our reputation. It makes us look like hypocrites when we criticize other countries that make frequent use of their blasphemy laws.

That the existence of the law damages our reputation was borne out as recently as 10 December. (International Human Rights Day.) That’s the release date of the annual International Humanist Ethical Union’s (IHEU) Freedom of Thought report. Once again, the existence of a blasphemy law in New Zealand meant we got a rating of “Severe Discrimination”. Other countries in that category are Russia, Rwanda, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Algeria, El Salvador, Myanmar, Palestine and Turkey. Australia and all the Pacific Islands (except Samoa) rate better than us.

You would think the government would be keen to remove this stain on our reputation, but no. In a statement to Radio New Zealand, Justice Minister Amy Adams said;

“I’ve indicated that my main priorities are to reduce the incidence of family and domestic violence and better protect victims of sexual violence, particularly during the court process. This work is underway and I have no current plans to change the programme to incorporate work on blasphemy law.” She said the Law Commission’s revised work programme for the 2014 to 2015 year had already been finalised.

Her main priorities are admirable, but it’s disappointing there’s no interest in even considering the issue.

New Zealanders have suffered at the hands of the blasphemy laws of other countries too. New Zealander Phillip Blackwood was arrested for blasphemy in Myanmar last year. Blackwood was a bar manager. He posted the image below on FaceBook to promote the bar. According to AFP via Stuff.co.nz, he is now “being held in the notorious Insein Prison in Yangoon”. If found guilty, he faces two years in prison. Ironically, his arrest was also on International Human Rights Day (10 December 2014),

In the wake of the murders in the name of religion in Paris, the Humanist Society of New Zealand and the New Zealand Association of Rationalists and Humanists have called for the abolition of our blasphemy law, a call I fully support. The law, they jointly state, protects “… religions, rather than religious people from discrimination.”

As John Murphy, president of the New Zealand Association of Rationalists and Humanists, stated in an interview with Radio New Zealand:

… there [are] a number of reasons it should go. Firstly because of the potential for harm in the future, because it’s on the books and it could be abused. And secondly, if it is dormant and not being used, then why is it in the Crimes Act?

He has a point, of course. The ideas that make up a religion enjoy a privilege in our society that other ideas don’t. This is a problem. We can’t rely on all future attorneys-general making the right decision. Our current human rights laws are good and so far have been up to the task. But, they are only laws and can therefore be repealed. New Zealand is one of only three countries worldwide that doesn’t have a constitution. Thus, New Zealanders don’t have a constitutional right to free speech such as that enshrined in the First Amendment of the US Constitution.

He has a point, of course. The ideas that make up a religion enjoy a privilege in our society that other ideas don’t. This is a problem. We can’t rely on all future attorneys-general making the right decision. Our current human rights laws are good and so far have been up to the task. But, they are only laws and can therefore be repealed. New Zealand is one of only three countries worldwide that doesn’t have a constitution. Thus, New Zealanders don’t have a constitutional right to free speech such as that enshrined in the First Amendment of the US Constitution.

We MUST be free to question ideas, wherever they come from. This is the very basis of the maintenance of democracy. As soon as you exempt an idea from questioning, you create a benefit for that idea. That in turn creates an opportunity for exploitation. There is this feeling among many that we cannot question deeply and sincerely held beliefs.

Questioning beliefs is a taboo we have to get over. It is the only way a society moves forward. Christians and Muslims, for example, should remember their origins. If Jesus and Mohammed hadn’t questioned the prevailing ideas in their respective societies, they wouldn’t have Christianity or Islam today. We make every advance in every area of knowledge by questioning the status quo. Religion shouldn’t be exempt from that.

Dame Lyndsey Freer, spokeswoman for the Catholic diocese of Auckland, confirmed she was oblivious to the existence of a blasphemy law in New Zealand in an interview on Newstalk ZB on Tuesday with Kerre McIvor, and that the she considered human rights laws and similar legislation had always done the job of protecting people. When pressed about whether mocking religion should be a crime she states:

I think we should respect the sincerely held beliefs of the world’s great religions. Certainly I think that should be so … a healthy society is based on respect. Hate speech is the very antithesis of … that kind of respect. Mockery so often takes the form of humour, and I think we have to have a sense of humour. We have to be prepared to laugh at ourselves, and to allow other people to laugh at us… I think that that’s healthy. It’s very important that we can laugh, but then again, there is a boundary. There is a line in the sand, beyond which humour can become seriously offensive…

It’s an interesting thing though, how you actually respond … we in the Catholic Church have had a lot of mockery. I remember taking a couple of cases to the Broadcasting Standards Authority for the South Park programmes, that were very, very offensive to us really. The way they depicted Pope Benedict and we actually lost. It’s just one of those things you know, sometimes you just have to ‘kick for touch’ and say, ‘oh well, that’s just the way it is. We are in a free society and thank God for that’. The Catholic Church has come under a lot of attack from Charlie Hebdo, and yet the day after the massacre, Pope Francis offered his morning Mass to the victims.”

Dame Freer went on to state that she thought the response should be to pray for the victims, all of French society, and also the perpetrators of such hate.

It’s a tough one. But we all, whatever our beliefs … need to just live by the Golden Rule … do unto others as you’d have them do unto you.

Personally, I wish Pope Francis had stuck to offering a Mass to the victims. When a few days later he said that a normal response to a friend insulting his mother was to punch him, I was appalled. For a start, with friends like Frankie, who needs enemies? Punching someone at the drop of a hat is neither a normal nor an acceptable response. Further, he’s effectively condoning violence as an appropriate response to satire.

Professor Peter Lineham of Massey University’s School of Humanities, also talking to Newstalk ZB, was, unfortunately, more supportive of retaining the blasphemy law, with, in my opinion, a lack of logic about the issue. In the interview with Rachel Smalley, Professor Linehan acknowledges the design of the law was to prevent criticism of Christianity in England around 300 years ago. Further, ” … this is no longer appropriate in our kind of society”. However, instead of abolishing the law, he proposes expanding the law to cover all religions:

Linehan: The reason why there has been so much tension and offence among Islamic people is because they are much more – Christians have probably grown hardened to sarcasm, the Virgin in the Condom affair etc etc … but Muslims remain still very sensitive, very easily offended, and I don’t think we should just say, “get over it”. I think the idea that anything’s fair, well, you look at what has happened and you can see that Muslims in the case of the cartoon back in 2005 [sic], and the case of Charlie Hebdo, because they reprinted those Danish cartoons, the feeling clearly from some is that this is offensive, and maybe the word blasphemy is not the word we’d want to use, but I think all faiths should have that sort of protection, I don’t think, I wouldn’t want to put Muslims on a special pedestal.

Smalley: No. But I would’ve thought they would’ve been covered by our human rights legislation.

Linehan: The human rights legislation is a little bit curious in the way it goes about it, because while it contains protocol, it doesn’t contain (inaudible) for prosecuting that kind of speech that is calculated to deride a religion. So that warnings can be given, but … the law doesn’t defend religion as such. In fact in many ways it protects the rights of individuals to hold their own views.

Smalley: So if it was scrapped … in New Zealand, who would stand to lose from that do you think?

Linehan: Well, I think in the first instance actually, anybody who holds a position based upon faith in some particular position would stand to lose. But since the law is very rarely enforced, and this is the problem with a law like this for me. The Virgin in the Condom case proved that it’s extremely difficult to get a successful prosecution today, because you’ve got to show that there’s calculable offence created within the religious community, so it would need to be a differently conceived law. But I would have thought that anybody in any faith position would expect that there could be criticism of their faith. But it would need to be done in a manner not liable to cause offence.

Smalley: Right.

Linehan: That’s where you’ve got to define it carefully because, I mean, you might get a Muslim who (inaudible) at any criticism of the Qur’an or the like. Well we can’t allow that I don’t think. I wouldn’t want to criticize the Qur’an – I’m not a Muslim.

Smalley: Indeed.

Linehan: So there you are – it’s going to be a hard one.

Professor Linehan has cruised into the ‘blame the victim’ camp here, which I find disappointing. Further, while acknowledging a person of faith can expect criticism, he thinks there should be no offence in the criticism. I’m not sure that’s even possible. How to you debate a Young Earth Creationist without coming across as mocking their views? Linehan’s putting religious thought into a separate box to other ideas, which is the whole problem with blasphemy laws. His acknowledgement that we need debate is positive though.

The late philosopher Ronald Dworkin, wrote in response to the reaction to the cartoons of Mohammed in Jyllands-Posten in 2006. In his piece The Right to Ridicule he wrote:

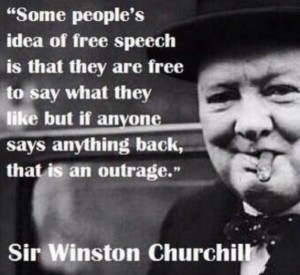

Freedom of speech is not just a special and distinctive emblem of Western culture…. Free speech is a condition of legitimate government. Laws and policies are not legitimate unless they have been adopted through a democratic process, and a process is not democratic if government has prevented anyone from expressing his convictions about what those laws and policies should be.

Ridicule is a distinct kind of expression; its substance cannot be repackaged in a less offensive rhetorical form without expressing something very different from what was intended. That is why cartoons and other forms of ridicule have for centuries, even when illegal, been among the most important weapons of both noble and wicked political movements. So in a democracy no one, however powerful or impotent, can have a right not to be insulted or offended.

Back in 2008, Rex Tauati Ahdar wrote an outstanding piece in the Otago Law Review entitled The Right to Protection of Religious Feelings, a piece that Amy Adams might like to read. Among several arguments he states:

…the price of the state protecting the right of religious freedom is that all shades of religious opinion are to be recognized and afforded protection. Religious people deservedly claim the right to bear witness to the truth. Yet much evangelism and proselytism – involving as it does the affirmation of contentious creeds (“the only way to salvation is through x” ) – involves explicit or implicit attacks upon or denials of other faiths. If we protect the positive assertion of religious truth in the public sphere in the name of religious freedom, we ought to equally protect those who refute, deny or scoff at the validity of that asserted truth. The same right that safeguards pro-religious speech protects anti-religious speech.

He concludes:

… that the case for a legal right to protect religious feelings is weak. The legal protection that has been afforded religious sensibilities to date is very limited, and that is how it should be.

I agree with him. Society has come to a place where we recognize the value of different opinions and dissenting voices. Disagreement must remain non-violent, and there should be space for all voices to present their arguments. Religion, in my opinion, has in any case proven it doesn’t deserve any special protection. So far, whenever it has been in a dominant position, religion has largely abused that privilege. Every other totalitarian belief system has done the same. Not only should we repeal our blasphemy law. New Zealand should become part of a call from all free nations to repeal them worldwide.

Many thanks to @SecularNZ, who was a great help in sourcing material for this article.

17 November 2017: Text edits made for clarity.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider donating a dollar or two to help keep the website going. Thank you.

I have just had a look at the provisions of the Crimes Act and was amazed to find:

“Every one is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 1 year who publishes any blasphemous libel.

(2)Whether any particular published matter is or is not a blasphemous libel is a question of fact.

(3)It is not an offence against this section to express in good faith and in decent language, or to attempt to establish by arguments used in good faith and conveyed in decent language, any opinion whatever on any religious subject.”

It certainly seems that the legislation no longer keeps pace with today’s society and the mix of religions now represented in New Zealand. What would be the outcome of someone casting dispirsions on Islam, Christianity or Buddha?

What if my religion was Jedi as many people identified in a previous census? I hope that no-one blasphemes against Yoda as I may move hell and high water to have them put in goal for 12 months.

I’d love to see Dr Lineham trying to write a law to cover the sensibilities of the Jedi!

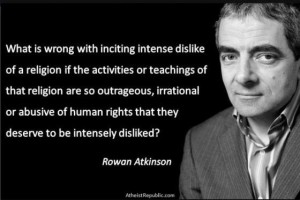

If someone sincerely believes in Nazism or white supremacy or a revolting creed like that we don’t have a problem with mocking them, and we don’t think the fact they’re a minority means we have to be careful. Religion has a privileged place in the spectrum of ideas, and that is simply wrong in my opinion. It has to be as open to scrutiny as any other idea.

(Tried to comment the other day, but I don’t think it went through):

Fascinating post – thank you for pointing it out to me!

Apparently, Canada too has a “blasphemous libel” section of the Criminal Code, but the Charter of Rights and Freedoms clearly overrides it. I guess the existence of this Charter (only adopted in 1982) is what formally separates Canada from NZ in the eyes of the Intl. Humanist Ethical Union’s report.

I agree with you though that I don’t see a good argument for retaining these antiquated laws. Is it really so difficult to strike them out? I don’t think so. I imagine the main reason governments are hesitant to do so is because they don’t want an opposition party turning it into a political issue. That’s a bit spineless, but also understandable.

Hi Ed. I think you’re probably right about Canada’s status in the IHEU report. I also agree about the reason politicians don’t sort this. They don’t want to upset any religious people. A lot of people here (not just religious ones because there aren’t that many) would have a gut reaction against getting rid of blasphemy laws because their initial reaction would be along the lines of respecting people’s religious views and they’d see that as a good thing. If you explained why they should be got rid of, most people would agree. Therefore, humanist, atheist, free speech, and legal groups that already know the arguments need to explain it to everybody first so there’s broad understanding of the issue. Then politicians would be happy to take up the cause. That requires getting journalists on board. The Stephen Fry thing might be the cause célèbre that makes this happen.

Thanks for your comment. It ended up in spam, probably because spammers usually target old posts to try and become approved commenters so they can then get their stuff on newer posts more easily. You shouldn’t have any more problems.

This update used to be at the end of the post, but was moved here on 16 November 2017 as part of an ongoing edit/upgrade of the post.

*Update 28 March 2015. Iain Middleton has let me know that I’ve got the origins of New Zealand’s blasphemy law incorrect. Rather than try and change my post, I thought I’d just add what he wrote.

Thanks Iain for this information. 🙂